The book

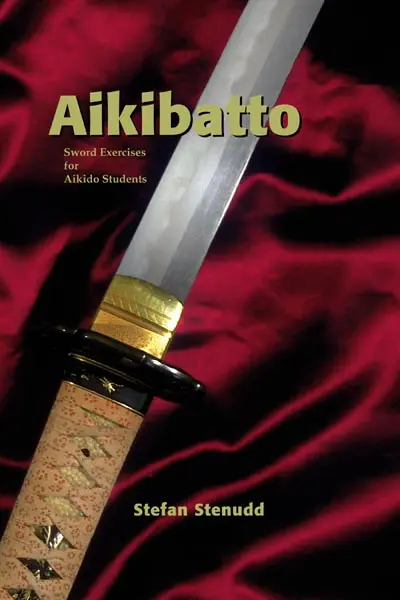

Aikibatto

Aikiken Sword Exercises for Aikido,

by Stefan Stenudd

Aikibatto is a system of sword (ken) and staff (jo) exercises for aikido students, as well as for anyone interested in the Japanese martial arts. In this book I present the basics and principles of the sophisticated sword arts developed by the Japanese warrior aristocracy, the samurai.

Click to see the book at Amazon >>>

Most aikido dojos practice with bokken, the wooden sword, and jo, the staff. It's usually called aikiken and aikijo, but there are other names for it — such as bukiwaza, kumitachi, et cetera. Unarmed defense against those weapons is called tachidori and jodori. Learning to handle the sword and the staff is very beneficial in aikido, which is to a large extent developed from the samurai arts.

Complicated Systems

The most common system of bokken and jo exercises is the one developed by Morihiro Saito. It's a very complex system with many different movements and techniques. Other aikido teachers have made their own systems, but they are very often variations on the Saito techniques, following their structure quite closely.

Another way of treating the sword and staff was developed by Shoji Nishio. He had studied the traditional arts of iaido and jodo at depth, and made his own system of combining these budo techniques with aikido movements. This also became quite an elaborate system, very difficult to master without profound experience of iaido and jodo training.

Aikido is in itself a vast and rather complicated system of techniques, taking lots of training. So, students often find themselves lacking proper bokken and jo skills, simply because they don't have enough time to train them.

If the exercises are many and strenuous to memorize, it often results in the students not getting enough of suburi, the drills in the basic movements of the sword and staff. They might remember numerous long kata, but their handling of the weapons is flawed.

That's what I wanted to approach with creating aikibatto. A limited set of exercises where the basic moves and principles of the Japanese sword and staff arts are trained sufficiently — and true to the traditions of those arts. The 101 of it, so to speak.

Originally I did it for my dojo members only, but then I reveived increasing interest from other aikido practitioners. So, I made a section on my website about aikibatto, and a few years later I wrote the book.

The Book

Although the aikibatto exercises are primarily developed for aikido students, they contain much of the normal curriculum of traditional iaido and kenjutsu. I hope that anyone interested in the arts of the

katana, the formidable Japanese sword, will find much of value in this book.

The book also contains extensive chapters on the spiritual aspects and the fundamentals of the sword arts, information about proper equipment, words on the teaching and learning aspects of aikibatto, and more. See the list of contents below.

How to get the book

If you want to buy the book, you can do so at most Internet bookstores. Click the image below to see the book at Amazon (paid link). The link takes you to your local Amazon store (or to Amazon.com).

Click the header to visit the book's Facebook page.

Table of Contents

Here is the book's table of contents:

Foreword 7

Background 9

Aikiken and iaido 10

The website 12

Aikibatto basics 13

Shoden and okuden 14

Distance and contact 16

Equipment 17

Reasons for aikibatto 35

Developing firm basics 35

A sword for the aikidoka 39

The teacher is the needle 45

Spiritual aspects 73

Do — the way 73

Tanden — the center 80

Ki — life energy 82

Sword art fundamentals 88

Posture 88

Grip 90

Cut 92

Aikibatto exercises 96

1 Shiho MAE 97

2 Shiho USHIRO 104

3 Shiho HIDARI 108

4 Shiho MIGI 115

5 Ukenagashi OMOTE 120

6 Ukenagashi URA 127

7 Kote CHUDAN 131

8 Kote JODAN 138

9 Harai ATE 143

10 Harai TSUKI 153

Aikibatto Jo 159

Introduction 159

Jo exercises 164

1 Shiho MAE 165

2 Shiho USHIRO 167

3 Shiho HIDARI 169

4 Shiho MIGI 171

5 Ukenagashi OMOTE 173

6 Ukenagashi URA 175

7 Kote CHUDAN 177

8 Kote JODAN 179

9 Harai ATE 181

10 Harai TSUKI 183

Glossary 185

Changes and additions 192

Developing firm basics

(a chapter from the book)

This is how it started:

As a member of the Swedish aikido dan grading committee, I was looking at some of my own students being examined. I had to admit that when it got to their performance with the bokken and jo, they did not all of them do as well as could be expected. In our dojo we do a decent amount of training with those tools, and I would like to think that the instruction is not completely off the track. I had thought that my students should handle it well, also on a dan grading.

But they made their series of movements with some awkwardness, almost in a mood of alienation. They could grip their tools acceptably, and swing them too – but in the combination of movements there was a lot of hesitation, making it all less convincing.

Immediately I understood that they were not to blame, but I was. They were just expressing the backside of a teaching method I had been using for the last several years – one of improvisation, of always making up new combinations in class, not sticking to any system of exercises at all. Inventing kata as we went along.

Improvised budo

In aikido one would say that it was in a spirit of takemusu, improvised budo, born in the moment. I still believe that it is a mighty essence in any martial art – well, in any art.

I had hoped that by this my students would not only learn the applied basics of how to use the sword and the jo, but also make their minds free enough to choose techniques according to circumstance – instead of sort of freezing, when things did not go exactly according to plan. I wanted to teach them creativity, an open mind, and the ability that goes with it.

Instead, some of them – well, most of them — were uncertain about how to move from one position to the next, what action with which to meet the opponent’s initiative, etcetera. They lacked firm understanding of how to apply their basic sword movements. Their improvisation became a random combination of techniques, sometimes in the right and functional places, sometimes not. Often they got completely lost in it.

It was clear that I had to rethink my teaching method.

From suburi to complexity

Myself, I have gone through a spectrum of teaching methods, through the years. When I started in the early 1970’s, we had lots of hours with Ichimura sensei, where we were standing in a circle doing more chudangiri, cuts to middle level, than anyone could possibly enjoy. There was more to his teaching, of course, but the suburi, the repetitive exercising of basic movements, was always near at hand.

Almost ten years later we were introduced to Shoji Nishio sensei. Although Ichimura’s teacher, he was a very different cup of tea. His movements were so complex and refined, it took us years – literally – just to perceive how he was moving. Not to mention how long it took to copy these moves, even in a very unpolished, clumsy way.

When struggling to learn Nishio sensei’s way of using the sword and the jo, I was grateful to have been forced to do such a lot of suburi, long before, not having to think of that as well. It would have been too much.

I could see, though, that students who had not gone through a sufficient amount of basic training before trying to learn Nishio sensei’s system, they had little chance of getting their basics right along the way. Quite the contrary. The many difficult and tricky moves seemed to seduce the students into ignoring the importance of basics – such as gripping, cutting, balance, center, and extension.

Anyone properly introduced into the sword arts would immediately say that without such basics, there is not much of a sword art remaining.

Actually, Nishio sensei also pointed this out. On one seminar, he suddenly interrupted the training of his complicated kata, to do some regular down to earth suburi. We did that basic training for a while, straightforward cutting exercises pretty much like in a normal kendo class. Then he explained to the congregation that this type of training must also be done.

It was for the local instructors to take care of, on a regular basis, so that when he came for a seminar, everyone could concentrate on what was more relevant for him to teach – that is, the stuff even the local instructors were not properly competent with.

Breaking up in parts

With this in mind, I decided not to teach my students the full and exact system of Nishio sensei’s ken and jo, but to break the kata up in small parts, do them in those small parts or mix them in different ways. This was to make my students focus on polishing the parts, instead of trying to rush through the complete combinations in a speed similar to that of Nishio sensei.

It worked rather well, I felt, especially in preparing the students for the Nishio sensei seminars. He visited our dojo several times during the 1990’s. I could see that my students managed to perform the kata he showed us, although they had not learned the combinations by heart. But they were familiar with the parts. So, I still believe this is a good way of preparing students for Nishio sensei’s system, if that is the goal.

On the other hand, this system of no system made my students lack in the ability to combine the parts convincingly. I realized that they were not enough familiarized with a way of doing so. Watching their efforts at that dan grading, I had to admit that some kind of system of exercises was needed.

Few movements, but all of them

Still, there was one thing to avoid: Too complex a system takes the student’s mind off the basics, and a competent handling of the sword risks to be substituted with a vast number of kata, all of them poorly performed.

So, a system of basic sword training had to be simple – much like the Seitei iai of ZNKR (Zen Nippon Kendo Renmei, the Japanese Kendo Federation): a limited number of forms, with a very limited number of movements in each. Actually, this is pretty much like suburi in disguise. A way for the students to practice the basic movements repeatedly, without being too bored by it.

Yet, the system would have little meaning if it were not to include all of the important movements, and most of the others as well – at least the ones not regarded as odd or exotic in Japanese sword schools. It would be good, too, if a substantial part of sword art terminology is used, to be memorized and understood in its context.

Furthermore, being primarily aimed at aikido students, such a sword exercise system would need to fit reasonably well with aikido strategy, movements, and principles. For example, in many sword art techniques, the evasive step usually called taisabaki in aikido, is absent. Instead, there is often a head-on movement of the body. Not so in for example Nishio sensei’s iaido system (he called it Aikido Toho), but certainly in the Seitei iai of ZNKR. If not, the latter would probably do fine as a system of basic sword exercises also for aikido students.

There is one more ingredient needed for the aikidoka: the partner training, the fencing if you will. Seitei iai could probably be trained in such a way, if some creative thinking is applied to it, but not ideally – especially not for aikidoka.

I needed a basic system, then, possible to train – without changing its forms — solo in iaido fashion, or with partner. That was to be aikibatto.

Samples

Here are two short chapters from the book, as Acrobat PDF files in computer screen resolution (72 DPI):

Spiritual aspects: Do — the way

1 Shiho MAE

About me

I'm a 7 dan Aikikai Shihan Swedish aikido instructor, member of the Swedish Aikido Grading Committee, former Vice Chairman of the International Aikido Federation and President of the Swedish Budo & Martial Arts Federation. I've practiced aikido and iaido since 1972. My iaido grade is 4 dan in

Aikido Toho Iai Kenkyukai, which I received from its founder Shoji Nishio in 1996. I'm also a writer of both fiction and non-fiction.

Aikibatto

Sword Exercises for Aikido Students

by Stefan Stenudd

Arriba Publ., 2007, 2009

Paperback, 192 pages

ISBN 978-91-7894-023-3

© Stefan Stenudd, 2000. You are free to any non-commercial use of this material, without having to ask for my permission. But please refer to this website, when doing so.

Aikibatto

My Other Websites

Myths in general and myths of creation in particular.

The wisdom of Taoism and the

Tao Te Ching, its ancient source.

An encyclopedia of life energy concepts around the world.

Qi (also spelled

chi or

ki) explained, with exercises to increase it.

The ancient Chinese system of divination and free online reading.

Tarot card meanings in divination and a free online spread.

The complete horoscope chart and how to read it.

Stefan Stenudd

About me

I'm a Swedish author of fiction and non-fiction books in both English and Swedish. I'm also an artist, a historian of ideas, and a 7 dan Aikikai Shihan aikido instructor. Click the header to read my full bio.