Cosmos of the Ancients The Greek Philosophers on Myth and CosmologyCritias he Athenian statesman Critias (c. 455-403 BC), who has given his name to one of Plato's dialogues and participates also in Timaeus, was a poet and thinker of distinction in his days. He was also Plato's uncle. When Critias seized the power and became one of the thirty tyrants, his rule was so terrible that he more than well earned the title. He died in battle, soon after that.

he Athenian statesman Critias (c. 455-403 BC), who has given his name to one of Plato's dialogues and participates also in Timaeus, was a poet and thinker of distinction in his days. He was also Plato's uncle. When Critias seized the power and became one of the thirty tyrants, his rule was so terrible that he more than well earned the title. He died in battle, soon after that.

His view on the gods, bluntly expressed in his satyr-play Sisyphus, goes in line with the forceful leadership of his. Critias claimed that the gods had been consciously invented, to frighten the people into obedience and a law-abiding life. Thus, the gods were all-seeing, so that no man could conceal his crime, and their abode was heaven, the far-off place which induced the most fear in man with its thunder, lightning and celestial mysteries. It is somewhat confusing that he put these words in the mouth of the Corinth king Sisyphus, who was, according to the legend, punished by Zeus for telling on an amorous adventure of the god, in the torturous way of having to roll a stone up a steep hill, just to see it roll down again, and to do it anew — forever. The rest of the play is lost to us, so in what phase of the story this speech is delivered, we do not know. It would make sense to occur before Sisyphus met with Zeus, and if so, he could by this be meant by Critias to express a hubris, which needed be punished with or without a disloyalty to Zeus adding to his crimes. That could imply a piety in Critias, writing a moral play on hubris and its punishment, though that seems less in character with the playwright than a flat agreement with what Sisyphus says. Whatever be the case, Sisyphus does in his monologue explain a process in society, a social cosmogony of sorts, which makes sense also to others than men of power: There was a time when the life of men was unordered, bestial and the slave of force, when there was no reward for the virtuous and no punishment for the wicked. Then, I think, men devised retributory laws, in order that Justice might be dictator and have arrogance as its slave, and if anyone sinned, he was punished. Then, when the laws forbade them to commit open crimes of violence, and they began to do them in secret, a wise and clever man invented fear (of the gods) for mortals, that there might be some means of frightening the wicked, even if they do anything or say or think it in secret. Hence, he introduced the Divine, saying that there is a God flourishing with immortal life, hearing and seeing with his mind, and thinking of everything and caring about these things, and having divine nature, who will hear everything said among mortals, and will be able to see all that is done. And even if you plan anything evil in secret, you will not escape the gods in this; for they have surpassing intelligence. In saying these words, he introduced the pleasantest of teachings, covering up the truth with a false theory; and he said that the gods dwelt there where he could most frighten men by saying it, whence he knew that fears exist for mortals and rewards for the hard life: in the upper periphery, where they saw lightnings and heard the dread rumblings of thunder, and the starry-faced body of heaven, the beautiful embroidery of Time the skilled craftsman, whence come forth the bright mass of the sun, and the wet shower upon the earth. With such fears did he surround mankind, through which he well established the deity with his argument, and in a fitting place, and quenched lawlessness among me ... Thus, I think, for the first time did someone persuade mortals to believe in a race of deities. This monologue is strikingly outspoken — Critias, through the voice of Sisyphos, expresses belief in no gods, no divine forces at all, just men and the deeds of men. To have been allowed such blasphemous utterances, even through the character of a play, he must indeed have been a man of importance in Athens, where Protagoras, just about this time, was driven out and his books burnt, merely for stating that the truth about the gods cannot be ascertained by man. And Critias went much further, claiming the gods not only to be invented by man, but also for such a worldly reason, where laws of men are given a higher power than those of the divine — heaven itself utilized for earthly ambitions. One marvels at the thought of his play actually having been performed afore the Athenians. The perspective of Critias is strictly political, another force in society than that of man himself he does not recognize. And man is, to Critias, in general not very impressive, his virtues rarely of noble origin: "More men are good through habit than through character." In Plato's dialogue given his name, Critias is again occupied with the subject of social powers — the mythical war said to have taken place some nine thousand years before, between majestic Atlantis and Athens, won by the latter in spite of its inferiority. That this man would view mythology as something of political origin is no surprise, and that his cosmology, though not explained in what is left of his words, must have been atheistic, is confirmed in another fragment of his: Nothing is certain, except that having been born we die, and that in life one cannot avoid disaster.

LiteratureFreeman, Kathleen, Ancilla to The Pre-Socratic Philosophers, Oxford 1952.

© Stefan Stenudd 2000

The Greek Philosophers

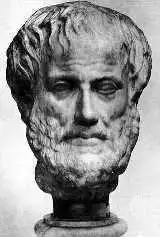

AristotleIntroductionAristotle's LifeTimelineAristotle's PoeticsAristotle's CosmologyAbout CookiesMy Other WebsitesCREATION MYTHSMyths in general and myths of creation in particular.

TAOISMThe wisdom of Taoism and the Tao Te Ching, its ancient source.

LIFE ENERGYAn encyclopedia of life energy concepts around the world.

QI ENERGY EXERCISESQi (also spelled chi or ki) explained, with exercises to increase it.

I CHINGThe ancient Chinese system of divination and free online reading.

TAROTTarot card meanings in divination and a free online spread.

ASTROLOGYThe complete horoscope chart and how to read it.

MY AMAZON PAGE

MY YOUTUBE AIKIDO

MY YOUTUBE ART

MY FACEBOOK

MY INSTAGRAM

MY TWITTER

STENUDD PÅ SVENSKA

|

Cosmos of the Ancients

Cosmos of the Ancients